On Being Ruderal

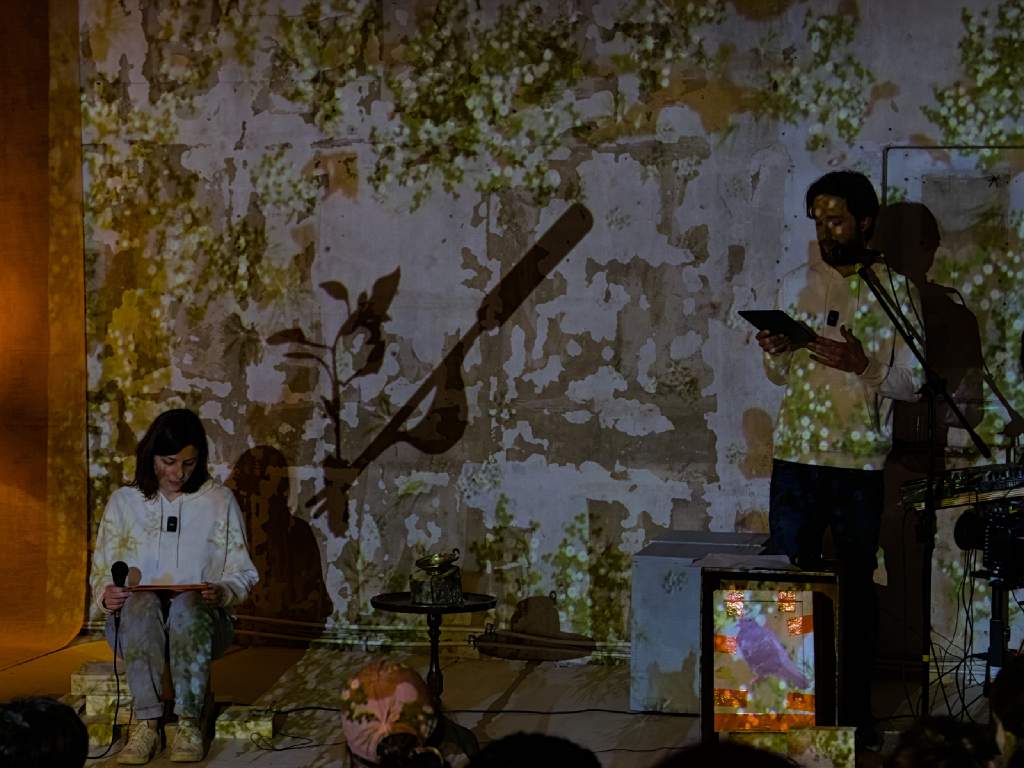

Lecture-performance, 30 mins, 2023. In collaboration with Thomas Mayer.

Photo: Juan Florez

Photo: Juan Florez

Photo: Juan Florez

Photo: Juan Florez

Photo: Mateo Walschburger

Photo: Juan Florez

Photo: Juan Florez

A lecture performance on spontaneity, adaptation, bad herbs, and unwelcome thoughts.

Text by Maria Paula Maldonado. • Visuals, animation and sound by Thomas Mayer. • Special thanks to Constanza Carvajal with whom we created the installation environment.

Part of the program Ruderal Practices organized by Make-up e.V. Generously funded by Stiftung Kunstfonds - NEUSTART KULTUR, and the Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien (BKM).

On Being Ruderal (Text)

I am a seed. I have no eyes. I can sense the light and I can sense the dark. There is movement. I am floating. I am light. I am being moved in different directions. The currents of air push and pull me. Sometimes very fast, sometimes gently slow. Sometimes the air stops and I free-fall. I can feel vertigo. I don’t know where I will land and where I will bloom. A seed is the manifestation of possibilities. I can feel the need to bloom. I may land on some of the richest soils or on the most eroded dust, in a dumpster or in the middle of a flood. I do not know.

I was born in a city that shares similar characteristics to other cities: it has buildings, streets and roads, transportation and communication networks, artificial lights, lots of people, a bit of chaos, and some public, some private and some green spaces. Cities are complex systems, full of layers, stories and negotiations. Cities have their rhythms, their movements, and their dwellers. La ciudad es un archipiélago / The city is an archipelago. There are all kinds of city dwellers: residents, workers, tourists, homeless people, students, immigrants, seniors, dogs, cats, pigeons, rats, trees, shrubs, flowers, weeds, and many other kinds of plants.

Cities are defined as human settlements of notable sizes1. These settlements are the product of different processes, one of which is displacement. Displacement for example of animals, plants, soils and water that used to inhabit and shape these areas. Along with displacement, and considering the processes of rearrangement, dislocation, relocation and transformation that take place for the formation of cities, it is reasonable to consider them –however comfortable they may be– as highly disturbed areas. It is not surprising, then, that from these troubled places, the idea of separation between humans (some humans) and nature emerged. On top of this separation, nature has been classified in different ways, for instance in four kinds: The “first nature” which refers to pristine and untouched natural environments, the “second nature” in reference to the rural and agricultural landscapes, the “third nature” to refer to gardens and parks which humans maintain, and the “fourth nature” in regard to the mutant, hybrid, emergent and spontaneous ecologies, where the natural is merged with the artificial and the technological2.

Even though nature is often conceived in cities as its background or as its decoration, there are varied interactions between humans and the multiple creatures that constitute green spaces in urban areas. Nature from the third and the fourth types are the most common ones in cities and it is possible to differentiate between one and the other depending on the care and maintenance that they received from humans. Initially, a lot goes to parks and gardens, and very little or nothing to plants growing in places not intended for their existence -as the vegetation of the fourth nature does not require human intervention to thrive-. Actually, we could even say that mutant ecologies corresponding to fourth nature could receive a significant but negative amount of human attention in the form of efforts to remove and exterminate them.

Attention is the key in order to think about another and more specific type of ecology related to the fourth nature but coined a few decades earlier. After the construction of the Berlin Wall, ecologists in West Berlin, who couldn’t go to their fieldwork areas anymore, shifted their attention and started looking inside into urban ecologies. What is the difference between coincidence and synchronicity? Through their observations, they recognized and studied specific vegetation which grew and flourished in the rubble and disturbed areas that remained in the city as a consequence of the destruction caused by war. They named these ecologies “Ruderals”.

Ruderal environments “refers to communities that emerge spontaneously in disturbed environments usually considered hostile to life”3 such as in rooftops, sidewalks, rubble fields, ruins and wastelands. As this vegetation is characterised by having fast-growing roots and by massively producing seeds4, ruderals are those indomitable plants, neither wild nor domesticated, that seem to appear everywhere. To go around aimless? They are the ones first to colonise disturbed lands and environments, as a result of natural causes, human actions or a mix of both.

Ruderal creatures –not only plants– embody spontaneity in their strategies and ways of growing and living. They pop up in any crack, any gap, any corner, any fissure and any interstice, and no matter how impossible it may seem to us, it is livable for them. Ruderals are opportunistic organisms who respond flexibly and adapt to the availability of scarce and/or changing resources. I am powerless to achieve anything worthy. In cities, where rich soils have been displaced and replaced by pavement, ruderal plants emerge from their alliance with dust5.

West-berlin ecologists also pointed out the migrant condition of some of the ruderal plants that they found in the city and that came from all over the world. “These plants, usually considered non-native species or weeds, hailed from warmer regions in the Mediterranean, Asia, and the Americas”6. Their seeds arrived in Berlin through various known and unknown means of transport such as soldiers’ or refugees’ boots, trains, and wagons transporting hay7.

As cities have displaced many of the native plants of the land on which they are built, and due to the warmer temperatures experienced in these urban areas, unexpected non-native plants have flourished together with other kinds of species. Ruderal plants do not care if they are called foreign, alien, extraneous, migrant, invasive, strange, unfamiliar or unwelcome. They do not ask for permission and do not apologise for surviving as they can. They do not follow the limits imposed by fences or by signs. On the contrary, they proliferate besides, above, under and in between the various inner borders and frontiers with which cities are organised.

Ruderals exist as heterogeneous ecologies. As such, they are the material counter-argument to the ideas of oneness and uniformity, so common in purist and nationalist discourses. Ruderals foster unintended encounters and all the entanglements and meshes that come out from them. Challenging the desires of alienation and the processes of othering, ruderals stand for the multiple, the earthly, the dynamic, the impure and the unsettled, especially nowadays after and in the midst of so many planetary disturbances.

Ruderal ecologies are equivalent to unruly worlds. They are stubborn and persistent. They are unintended and therefore unpredictable and unavoidable. They are indisciplinadas. Alone or in conjunction with other entities, ruderals rebel against order and predetermination. They defy authorities, the same ones that they do not even recognise. They are interrupciones. They interrupt and mess with the fantasies of uniformity, perfection, purity, sterilisation, progress and optimisation. They rebel against the violence of the “right ways” –the right way to do, the right way to think, the right way to live, the right way to be–.

Depending on specific contexts and relations, ruderals can be either noxious or benign, healthy and regenerative. Based on the situations, ruderals are to a higher or lesser extent unwelcome. Often overlooked, ruderals grow in dark corners and unreachable places. Mistaken for and intermixed with weeds (Unkräuter) and undergrowth, ruderals are undesired and uncomfortable.

Mala hierba nunca muere (Bad herb never die). I have always found this “dicho” very ridículo.

Just like ruderal beings, ruderal thoughts are uncontrollable. They also grow in the cracks, the gaps, the corners and the shadows of the mental spaces we inhabit. As with material environments, psychological ruderal ecologies, depending on the internal climate and external situations, produce desired or undesired thoughts, and therefore welcomed or unwelcomed feelings. Ruderals can pop up spontaneously and unexpectedly in the form of random ideas, images or words that could even escape uncontainably from the mouth out loud. When neglected, these thoughts can also proliferate and invade the mind, filling it with ideas and conversations which, like a broken record, play over and over again.

Ruderals produce gut reactions. They are felt in the stomach and in different parts of the body, from deep within our organs to the outermost layer of our skin. They are symptoms of disturbances, caused for example by anxiety, stress, pressure, exploitation or oppression. They can arise from the suppressed forces that want to find their own voice, their own shape and their own space. Ruderals, as their name suggests, can be rude and inappropriate. They are rude signs showing that something is going on and claiming attention. Claiming our own attention, not the attention that is extracted and exploited from us for the profit of a few others.

Plants, as most thoughts (because let’s face it, there are some horrendous thoughts), are labelled as “good” or “bad” depending on the place where they are growing and the space they are taking. Please think about what you want. Do they itch? Do they sting? Do they hurt? Do they heal? Do they give comfort? Do they suffocate?

Uncomfortable or not, ruderals are catalysts inviting connection and regeneration in disturbed and eroded worlds. Worlds that are connected to each other. “Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something.8” Overlapping and dynamic worlds with shifting intersections. Worlds inhabited by ruderal beings who, just as they do not recognise authorities, do not recognise frontiers. They do not recognize boundaries between inside and outside, between the separate and the continuous. Ruderals stand against alienation and isolation and against monocultures of all kinds.

We live on a disturbed planet. El planeta es un archipiélago / The planet is an archipelago. The first nature no longer exists. It has been covered by radioactive material and microplastics. It has been decimated and has suffered a significant amount of losses, some of them irreversible. There is no way back. But there are many ways to continue: forwards, backwards, in circles, into unknown paths, or, as with ruderals, into the cracks. Visible or invisible, tiny or huge, cracks are full of life and full of possibilities of livability. Into the cracks where more and more seeds –ruderals and of all types– can grow, bloom and flourish.

Let us be careful: Beyond being our companions, ruderals can be our guides, but to a certain extent; because systemic injustices, happening all over the world, cannot be overcome and avoided by being more spontaneous, adaptable and flexible, by working or by trying harder, or by writing affirmations, positively manifesting and being more mindful.

Todos somos archipiélagos / We are all archipelagos.

How about resisting the urge to pull ruderal plants, ruderal thoughts and ruderal beings out of the cracks? Resisting the urge to garden or to exterminate them? Perhaps we should better focus on restoring our grounds9. Allowing ruderals to be. Creating and preserving heterogeneous contexts in which the relations are healthy and rich, instead of damaging and exploitative. Living with unlikely neighbours10 and bearing gracefully contradictions. Discerning when to fertilise and when to leave alone.

Because everyone and everything carries their own little ruderals and weeds. Suppressing and ripping them out is not the solution. They will carry on being messy, and unruly, they will be back (because they never left in the first place), and they will continue to grow.

Note: Thumbnail photo by Juan Florez

-

“City,” in Wikipedia, March 16, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=City&oldid=1158771152. ↩︎

-

Encuentros En La Cuarta Naturaleza, Con Pepe Galdeano y Malú Cayetano, accessed March 15, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F_Kv3ycxfyY. ↩︎

-

Bettina Stoetzer, Ruderal City: Ecologies of Migration, Race, and Urban Nature in Berlin (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2022), 3. ↩︎

-

“Ruderal Species,” in Wikipedia, March 15, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ruderal_species&oldid=1149663291. ↩︎

-

Alie Ward, “Indigenous Pedology (SOIL SCIENCE) with Dr. Lydia Jennings,” Alie Ward, November 23, 2022, https://www.alieward.com/ologies/indigenouspedology. ↩︎

-

Bettina Stoetzer at Ruderal Ecologies 2 “Ruderal City,” accessed March 19, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOgqSKAdTgo. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, First Edition edition (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2016), 31. ↩︎

-

Jenny Odell, How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2021), 155. ↩︎

-

Bettina Stoetzer, Ruderal City: Ecologies of Migration, Race, and Urban Nature in Berlin (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2022). ↩︎

- Posted on:

- March 25, 2023

- Length:

- 10 minute read, 2100 words

- Categories:

- x

- Series:

- Getting Started

- Tags:

- x